One of the main non-negotiable expenses on a grass farm is fencing. One way or another, you’ve gotta keep the animals in. There’s a ton of different options, and all have their upsides and downsides. Treated posts are readily available, but can’t be used on organic operations and like to bust when you accidentally hit them. Black locust or osage orange last super long, but can be harder to source, harder to work with and more expensive. The newer PVC posts are a great emerging option but still cost a pretty penny.

What if you could get fence posts that are cheaper than the ones mentioned above, and will last over 100 years? Not only that, but these fence posts will provide shade, build soil, add carbon and nitrogen, and drop feed for livestock and wildlife. Sounds like a pretty magical fence post.

As you likely guessed (or knew from the outset because, well, what else do I write about?), I’m talking about trees.

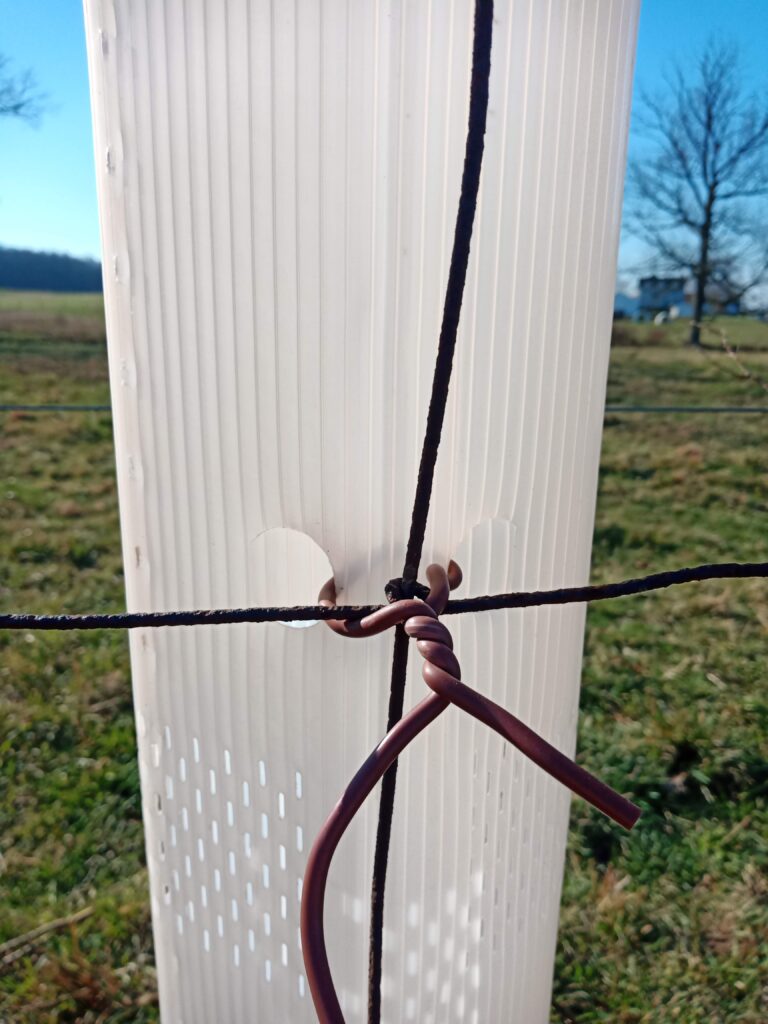

Now I know what you’re thinking: “Don’t attach your fence to the tree! The tree will swallow it up and cause a mess. Pity the person who has to cut that tree down some day.” And you’re 100% right. But I’m not talking about attaching a fence directly to the tree. Rather, we nail a small board to the tree first, which the tree will push out as it grows. The fence hardware is attached to the board, so that it never gets swallowed up by the tree. It’s super simple, cost-effective, and you can make it with materials you likely have on the farm already. The pictures will show you in better detail than I could with words.

I wish I could claim this silvopasture innovation as my own, but I first learned it from Brett Chedzoy, a grazier and forester in Watkins Glen, NY. It’s an amazingly simple trick that hasn’t gotten the publicity it deserves, likely because it’ll never make any one company any money. But it can save thousands of farmers thousands of dollars in fencing, while bringing more life to our farms.

Let’s break down the numbers a bit. I just called a local fencing supplier, and they were charging $16 for 5” 7’ treated posts, and $22 for 4×4” 8’ locust posts. Timeless Fence is listing their 1.75” 6’ T posts at $10. Those will be our references.

The cost of the tree is the big variable. If you already have a tree in place, obviously your tree cost is zero. If you have to plant a tree, your cost will depend on what stock you use. If you use bare root seedlings, we’re talking less than $2 in most cases. If you want grafted trees for high quality fruit, be prepared to pay $30, but then we’re talking about getting a whole lot more value than simply a fence post. So let’s assume we’re using a $2 bare root seedling.

If establishing a tree along an existing fence, your other cost will be a tree tube to keep the tree protected while it gets to size, while insulating the electric fencing from the tree. Because there’s an existing fence, you shouldn’t need a stake, as you can tie the tube directly to the fence and hold it up that way. We use and sell Plantra shelters, and a 6’ tube runs for about $5.70. That brings your materials cost up to $7.70 per tree. The board, nail and washers will add another $3-5, depending on what wood you’re using. There are of course also cost-share options for tree planting in many states. The folks at Working Trees, which pays farmers for the carbon sequestered when planting trees in pastures, would be able to cover a good portion of those material costs, reducing your input even further.

As far as labor is concerned, my estimate is you’re probably going to install the trees and shelter faster than you would a fence post, and you’ll certainly need less machinery and diesel than with heavy wooden posts that need a post pounder or auger to install. But the tree will need more care as it gets established, plus the board attached, so let’s call it a wash for now.

What we get is a real reduction in fencing cost, especially if you tap into cost-share. And if you want silvopasture trees anyway, this simply kills two birds with one stone. Or rather, you give two birds a home with one tree.

The two main limiting factors here are time and permanence. If you’re installing a new fence and you need it now, trees as living fence posts are obviously not the way to go. If you need to replace existing fence posts and your old ones have another year or two left before they need replaced, trees won’t be there in time for you. If you’re leasing land like Greg Judy and need to be able to pull up hardware if a lease gets terminated, you’ll find trees are tough to uproot and install somewhere else. But if you’re able to plan ahead and give yourself 5 or so years runway, and know you’ll be there long-term, trees offer a great opportunity to reduce the costs of an expensive input on your farm, while shading your stock and creating a more diverse, rich and beautiful farm.

If you’d like to start using trees as your long-term fence posts, here’s how I recommend going about it:

- First, use the trees you already have, if you have them. That’s the easiest, cheapest and quickest way to start. The main exception is trees that would have high-value timber potential down the road, like black walnut, of which you don’t want to damage the wood

- Encourage and train young trees that want to come up along your fence line anyway. In my area that’s mostly mulberries and black walnuts, though other trees will also come up as well.

- If you don’t have existing trees to work with, plant trees that will get up to size in time for you to replace your current fence posts. If you’ve got 5+ years, you have plenty of options. Less time means you’ll need to prioritize fast-growing species, which often have shorter lifespans.

- This is a great opportunity to select trees for biodiversity. Fence trees won’t be timber trees, and if they’re on your property boundary, you don’t necessarily want half of the fruit, pods or nuts dropping on the neighbor’s land or the road. Species like basswood or tulip poplar are great for pollinators. Crab apples can provide abundant food for wildlife, redbuds have beautiful spring flowers, and big old sycamores are about as majestic as trees can be. You get the picture. This can be a great spot to create more diversity and beauty on the farm.

- Even trees that typically have a short lifespan can be good options, if managed well. Willows for example will typically last only ~30 years, but if regularly cut back, they can last for 100+ years [I write more about using willows for fodder here]. The fact that willows can be propagated cheaply and grow quickly make them interesting candidates for living fence posts, especially in wet areas.

This is just one more way trees can be used to transform grazing by reducing costs and stacking functions. Now let’s put it to use and see how regenerative and profitable grazing can be.