It may come as a surprise to you that the most productive, best pasture in the country is not on some rich flat soil in the middle of Iowa, nor in the fertile rolling hills of Lancaster County Pennsylvania. Rather, the best pasture in all of the United States may just be on a humble Virginia side hill.

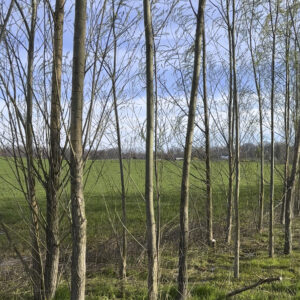

What’s more surprising still is that it’s not really on a farm. It’s part of a research plot at Virginia Tech. It’s not featured in glossy magazines, and the folks who manage and measure it are not out on the speaking circuit. The forages are good, but not great. It is, after all, on a low-input Virginia side hill that wants to grow fescue above anything else. What makes this pasture truly stand out is not the forages, but the trees that rise above it.

Back in 1995, a trial was set up at Virginia Tech to study how trees would affect forage and livestock performance as part of a larger agroforestry research and demonstration site. Open pastures serve as the control, while black walnut trees were planted in one set of experimental pastures, and honey locust trees in the third set of pastures. Thankfully these were not just any old thorny honey locust. They were grafted, high-yielding types, specifically the Millwood variety. They were there to produce feed, and they’ve done so by the truckload.

While we could dwell on the benefits of wildlife habitat or increased soil organic matter, nutrient cycling or reduction in parasite loads, there are two main reasons this pasture stands out above the rest:

- Tons of free feed stockpiled for the winter

- Reduced heat stress on livestock, and hence higher production

Let’s first look at the stockpiled feed. While everyone recognizes the value of shade for livestock, few have been aware that trees, especially honey locusts, can supply tremendous amounts of feed. The critical factor here is that the feed is available at the most necessary, most valuable time of year: winter. As Jim Gerrish points out in Kick the Hay Habit: “In the active growing season, and particularly in the spring, the alternative to a cheap bite of grass is another bite of cheap grass next to it. On the other hand, during winter the alternative to a bite of low-cost stockpiled pasture is high-priced hay.” Each bale of hay you can avoid feeding in the wintertime means more cash in your pocket.

When it comes to yield of pods, we’re not talking about a garnish. In 2015, these 20-year-old trees at Virginia Tech yielded 4,300 pounds of dry matter pods per acre, while the forages beneath the dappled shade of honeylocusts yielded just as much as an open pasture. I’ll restate that, so we’re completely clear: there was zero loss of forage production, and each acre yielded 4,300 pounds of additional dry matter in the form of honeylocust pods. The pods are a bonus, and a huge bonus at that.

To put that 4,300 pounds of pods into context, that’s equivalent to 91 bushels of corn, all produced free of charge and eaten right there in-place by the livestock. And while the energy in corn is from starches, the energy in honey locust pods is from sugars and pectin. Pound for pound, honey locust pods have roughly twice the energy (calories) as hay, making the pods a valuable high-energy complement to typically low-energy forages, and are made available during the cold months when energy is most needed. Once planted, the pods are produced for free, with no inputs of fertilizer, machinery or diesel fuel, while the trees provide shade, fix nitrogen and add to the soil biology.

Now I would be wrong to not point out that this was a really good year for those trees. Like apples, honey locusts will bear heavy in some years, and light (or not at all) in others. Thankfully, trees don’t all sync up their production into masting cycles like oaks do. Since all the trees in this plot were of a single variety (Millwood), they all tend to cycle through years of high and low yield together. The simple solution is to plant multiple grafted varieties, as well as some seedlings. While annual yields have not been precisely tracked, even if the trees took the next year off completely, the 2-year average would still be 2,150 pounds.

Let me underscore again the critical value of the timing. If these pods were dropped in May and June, the additional value would be real, but not nearly as valuable as a high-energy feed that drops when nothing else is growing (November-January). This allows you to supplement your stockpiled forages with the high-energy feed livestock need to keep warm, maintain condition, and continue producing right through winter. Between a well-managed forage stockpile and a good planting of honey locust trees, grazing 365 days a year is very well within reach.

As if all the extra free feed wasn’t enough, the other large benefit is the shade that’s provided by these trees. We know that heat stress kills production, which is why graziers go to great lengths to provide shade for their animals. Yet while most make do with a few overburdened shade trees, or schlep expensive shade mobiles around their pastures, the livestock at Virginia Tech enjoy nice, dappled shade that moves about the pasture all day long, never allowing animals to congregate in one place for too long. This well-managed tree system avoids the extremes of too much sun or too much shade to create a cool, moderated microclimate where livestock and cool-season forages thrive.

My goal in this is to show just how much room there is for growth in the field of grazing. By learning to integrate trees with grazing systems we can produce more per acre, and spend less in the process! This means that perennial, pasture-based farming can become that much more profitable, and completely outrun conventional, annual, input-intensive agriculture. It means that grass farmers will earn more money and hence control more land, which in turn means we will all enjoy better water, cleaner air, and healthier food. It means we’ll create more organic matter in the soil, store more water in rain events, and add billions of new microorganisms to the earth beneath our feet. The trees will give grass farmers a powerful, visible means of telling their story to customers, a story that beats any other food narrative out there.

This pasture at Virginia Tech is great, but in no way is it the ideal, the pinnacle of perfection. It merely points to what can be if we apply a combination of creativity, patience and stewardship. Simply by planting the same trees in Iowa or Lancaster County you’d be starting from a much better base, with deeper soils and lush, vibrant forages. Then add more tree diversity, like oaks, mulberries and persimmons for hogs, conifers for a windbreak, and chestnuts to roast over an open fire. Get some more livestock diversity in there, and watch the symbiosis develop. Keep improving on the honey locust genetics to get higher yields and more consistency year-to-year. Get someone like John Kempf out there to coax better yield from the trees. The possibilities are endless.

Here’s the takeaway: with silvopasture, we can create low-input, high-output, high margin farms that restore our farm ecologies in the process. We can take grazing to whole new heights. Let’s go see just how regenerative grazing can be.